Correlation vs. Causation: Why Correlation Does Not Imply Causation

In the data analysis and decision sector the terms correlation and causation are quite often confused, however, they are not synonyms, and here are the reasons why:

TL;DR

- A correlation does not imply causation, but causation always implies correlation.

- The third variable problem and the directionality problem are two of the main reasons why correlation does not imply causation.

- Use correlational research designs to identify the correlation between variables, whereas you should use experimental designs to test causation.

Terminologies Explained

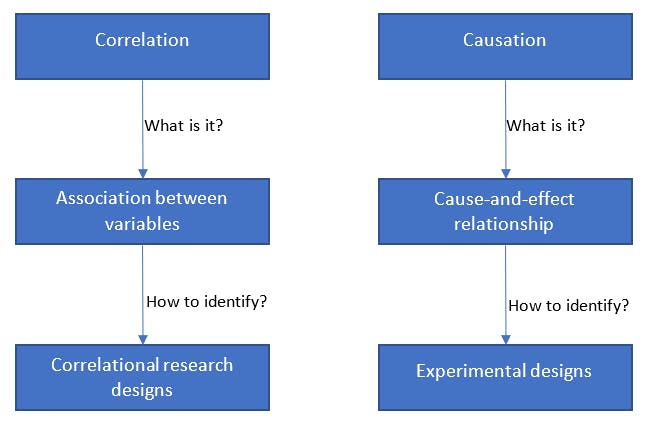

Correlation

Correlation means there is an association between variables, i.e. when one variable changes so does the other- put it more simply, it's when the variables of your dataset look like they are moving together in some way. More specifically, a correlation reflects the strength and/or direction of the association between two or more variables: a positive correlation means that both variables change in the same direction (e.g. when x is higher, y tends to be higher), whereas when the variables change in opposite directions there is a negative correlation (e.g. when x is higher, y tends to be lower). And as expected, a zero correlation means that there is no relationship between the variables.

In other words, when there is a correlation between two variables then those variables covary, and that represents a statistical indicator of the relationship between the variables. However, the reasons behind this covariation are not necessarily because of a causal link (causation), neither a direct nor an indirect causal link. Instead, there are mainly two reasons why correlation is not causation: the third variable and the directionality problem. Let's break them down:

Why Correlation Is Not Causation

The third variable problem describes that there is a third variable called confounding variable) (also called confounder or confounding factor), that affects the two correlated variables in a way it makes them seem causally related when in fact they are not. For example, in the summer the increase in the number of people going for a swim and the increase in violent crime rates are closely correlated, but they are not causally linked with each other because, of course, the former does not cause the other, and vice versa- what is happening here is that there is a third variable, that of the hot temperature, that has an effect on both variables separately.

And the second main reason comprises the directionality problem, which occurs when two variables correlate and might actually have a causal relationship, but there is no way to infer which variable causes the change to the other variable - you can think of that as the What came first, the chicken or the egg problem (although this seems to have been finally solved. For example, studies have shown that vitamin D levels are correlated with depression, but it’s not clear if low vitamin D causes depression, or if depression causes reduced vitamin D intake.

Note that when you want to describe the correlation between variables, it is correct to use the word relationship instead of association interchangeably, but not causation, because:

Causation

Causation (also known as causality) means that changes in one variable entail changes in the other. Here a cause-and-effect relationship exists: the two variables are correlated with each other and there is also a causal link between them. The events of the causation might take place either at the same time or successively one after the other.

Last Thoughts

All in all, a correlation does not imply causation, but causation always implies correlation. It is essential to distinguish the terms in order to infer if causality exists when two variables correlate with each other, or if they are simply correlated without a cause-and-effect relationship. For example, if you optimized part of your app during the last month and at the same time a significant increase in your app downloads occurred, then you would like to know if that particular optimization brought more users, or if it was just a coincidence.

But how can you test your data and claim if causality exists when correlation incurs? Well, you may use correlational research designs to identify the correlation between variables, whereas you should use experimental designs (e.g. randomized and experimental studies, quasi-experimental studies, etc.) to test causation.